SEVENTY years ago, in the dying days of the Second World War, more than 80,000 prisoners of war were forcemarched hundreds of miles across Europe by their German captors.

As the Russian Army advanced, the prisoners of war were forced westward with frostbitten feet in raging snowstorms, in what became simply known as the March.

Almost 3,500 are believed to have died.

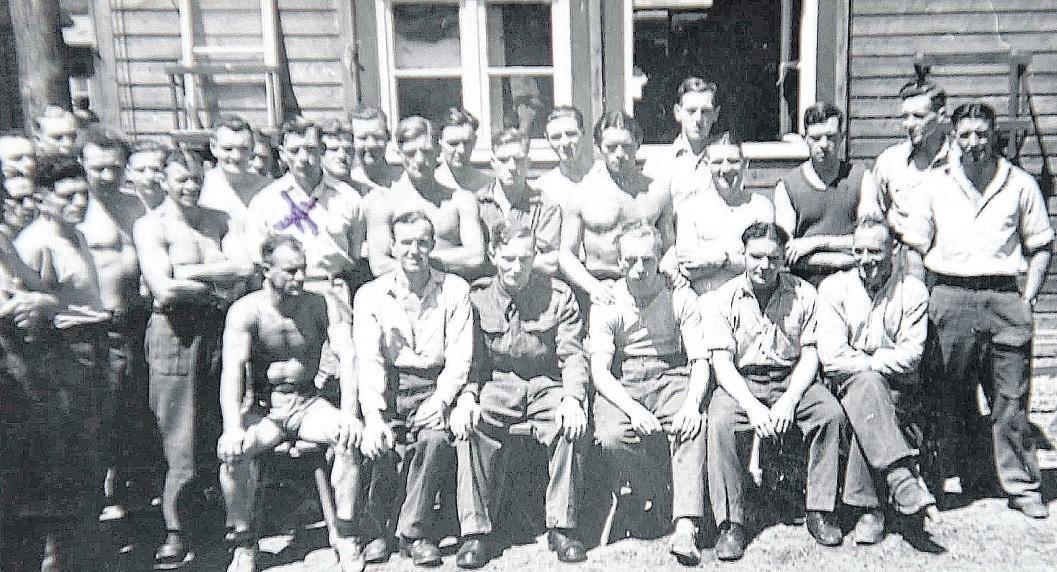

Ralph Teasdale, 96, from Clacton, pictures below, was among those who survived.

He wasn’t even old enough to have a pint when he was conscripted at the start of the war – you had to be 21 to drink alcohol at this time.

He joined the Northumberland Fusiliers, but was transferred to the Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders.

He admitted: “I was more frightened of the Scots than the Germans – there were a few wild ones among them.”

By May 1940, he was fighting a rearguard action as the German blitzkrieg pushed through the Ardennes and into France, where the British Expeditionary Force was retreating.

Ralph, of Arnold Road, said: “They came through Belgium and Holland – they just swept through. We didn’t have a chance. We only had old-fashioned rifles and bayonets.

“We were told to make our way toDunkirk. We didn’t know about all those little boats coming over.

“There were tanks to the right of us and tanks to the left.

People below me were getting shot and, then suddenly, the engine went up.

“We jumped down to the La Bassee Canal below the road. A German in a black uniform came up and said ‘handy-ho’.

“We presumed it meant put your hands up, but some were a bit slow and he just shot them.”

Ralph survived, but other British troops were massacred in cold blood.

The Royal Norfolks had been in the next field. When they surrendered, an SS division took the unarmed men to a farm and machine-gunned 97 British prisoners.

Ralph was held at a series of PoW camps during the war, including three years at Blechhammer, near Auschwitz, Stalag 22b and the notorious Lamsdorf.

At Blechhammer – Ralph Teasdale, fourth from the left in the second row, marked with an X

He pretended to be a carpenter to get better treatment.

Ralph said: “I worked as a carpenter for seven months, even though I didn’t know one end of ahammer from the other.

I just tried to look busy. I was always putting a screwinor taking one out.

“You’d get a pat on the shoulder and the guards would say ‘good Englander’. They thought I was working, but I wasn’t.”

In one camp, the PoWs distilled alcohol from food parcel raisins at Christmas.

Ralph said: “We’d sacrifice a couple of bedboards to get the stove going. It went through a copper pipe and then the steam cooled and came out a drop at a time.

“You stood in line with a dessert spoon. I don’t knowhow strong it was, but it was powerful stuff. You never got your second lot because you fell down unconscious.

“Some guards would kick it over so you lost the lot, but others thought if they want to kill themselves, then let them.

“You had those moments like that – you had to. You just had to grin and bear it and hope for the best.”

Ralph thought they were making pigswill in the camp kitchens, but discovered it was for Jewish concentration camp prisoners.

The PoWs would throw empty ration tins over the barbed wire to the Jews, who scraped them clean.

As the tide of war turned, the Russians began to push towards Berlin.

The Germans started to empty the PoW camps in the east and force-marched thousands of PoWs west, away from the advancing Red Army.

The march took four months and covered up to 1,500 miles across Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Germany, in appalling subzero winter conditions.

Ralph said: “We were awoken at 3am on January 21 and told theywere going to take us to the US lines.

“They said theywere going to save us from the Russians. But if you are being saved, you don’t usually have a machine gun pointing at you.

“Everyone seemed to be on the march. We found out we weren’t anywhere near the Americans – we were just going round in circles. I don’t think they knew where they were going – we just went west.

“Whereverwewent there was snow. People were dying by the roadside, but you just had to keep going.

“We stayed in barns. You daren’t take your boots off because they froze and you couldn’t get them back on the next morning, or they would be stolen in the night.”

Ralph managed to escape with twoAustralians andaNew Zealander.

The PoWs dived through an open doorway as the exhausted column trudged past, unseen by the German guards.

They walked at night and hid by day. A Czechoslovakian guest house gave the fugitives bread and dripping. Ralph said: “It was beautiful. It was like the best meal we had ever had.”

They were on the run for a month before being recaptured.

The four were put in jail where local girls brought them bacon, but eventually they ended up backwith the column.

Ralph said: “Wewere paraded in front of the commander who told us not to escape again or we would be shot.

“He said if we stayedwith the column, each man would get six or seven cigarettes. Cigarettes were currency then, everyone smoked. Just the thought of cigarettes kept us in that column.”

He was eventually liberated by the Russians.

After the war, Ralph became a relief signalman on the railways.

He moved to Clacton in 1999, with wife Betty.

He said: “My daughter was a teacher and ended up at Clacton County High School, so we decided we’d come to Clacton.”

What sticks in Ralph’s mind most about his experience is the hunger. He said: “The best thing you would get to eat would be a boiled potato. You just existed.”

Click here to read more stories like this in the Gazette's history section

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel