Colchester claims it’s Britain’s Oldest Recorded Town. Fine. But can it also claim the Oldest Recorded Hot Cross Bun? Is it time to make a call to Guinness World Records? Colchester historian Andrew Phillips turns detective...

THE EVIDENCE

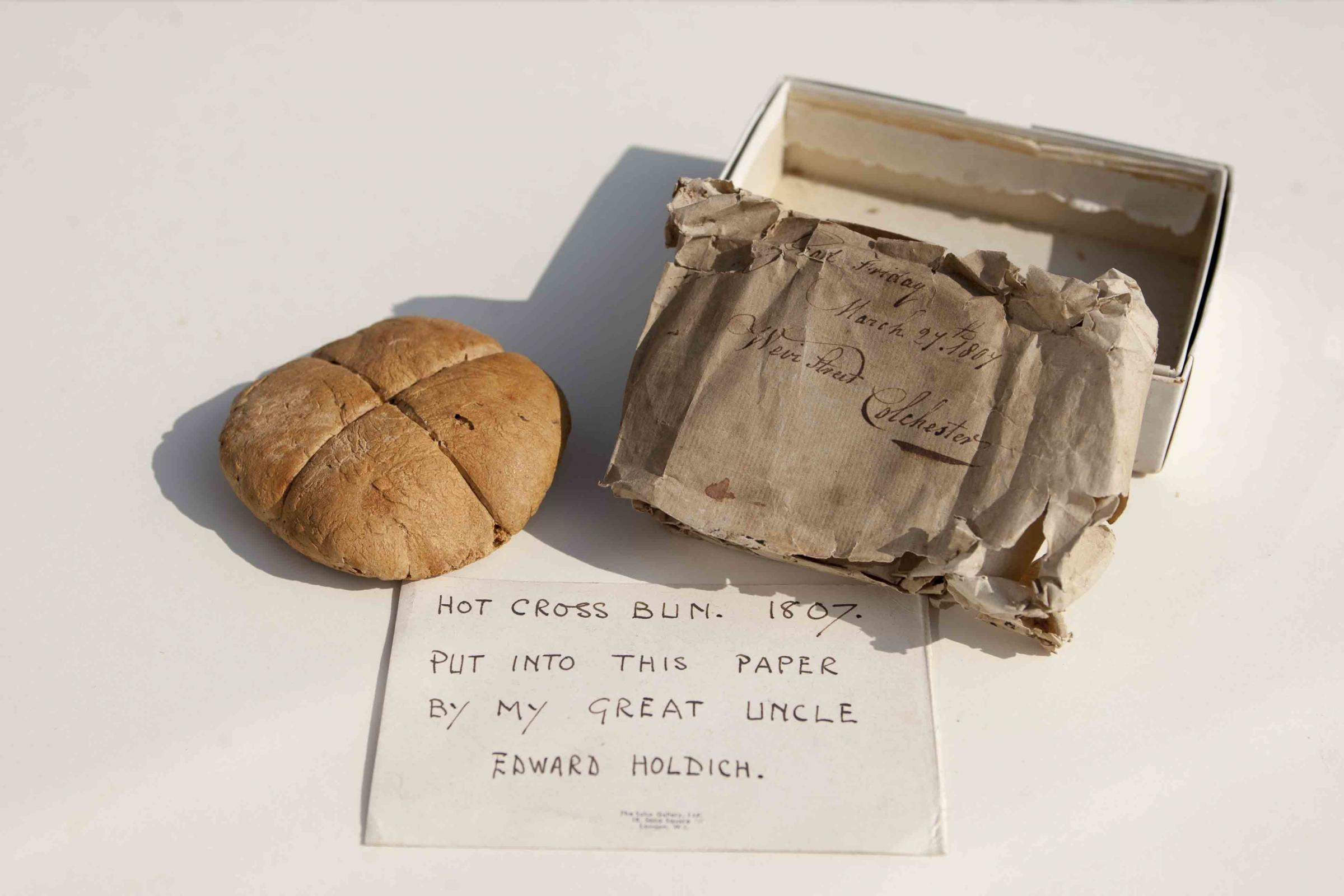

In 2013, the Gazette ran a feature about an ancient cross bun owned by Andrew Munson of Wormingford.

He had been given it 37 years before by his eccentric neighbour, Norman Baker, as thanks for fixing his electrics. The bun is rock hard, Andrew said, like Polyfilla.

If you look at Andrew’s photo you can see the cross is cut and the bun is a small bread roll. Encouraging. Hot cross buns were originally just fresh bread rolls – er, 214 years ago.

The bun came with an original paper bag. On it is written “Good Friday March 27th 1807 Weir Street Colchester”. The handwriting is authentic 19th-century copperplate. Weir Street is clearly Wyre Street, a common spelling at that date, another authentic sign. Then, as now, Wyre Street had shops likely to sell hot cross buns.

With it came a note, perhaps a copy of an earlier version, on an envelope owned by John Baker of London, saying it was ‘Put in this paper by my great uncle, Edward Holdich’. So who was Holdich, and who wrote the note?

MYSTERY. The oldest hot cross bun in the world? the evidence

THE SEARCH

As family historians know, internet access to births, deaths and censuses enable you to track down Victorian individuals, but dates before 1840 are tricky.

Fortunately Holdich is a rare surname. All Holdiches stem from the same area and Hol-dich means deep ditch and would have begun around 1300 with a man called John de Holdich.

Five centuries later his descendant, the Rev Jeffrey Holdich, was vicar of Stibbington on the edge of the Fens, a job he held for 50 years.

His younger son, Edward, became apothecary (pharmacist) to the royal family; another son, Jeffrey, became a doctor in Hornchurch. This Jeffrey had three sons: Richard, born 1772, became a doctor; William, 1774, also a doctor, while Edward, 1773, broke the medical rule, becoming a London draper.

Edward married a wife in Colchester and moved there. So we have found Edward Holdich in Colchester in 1807.

The plot now thickens. Edward Holdich had five children, four of whom died in infancy or early childhood. From their births, christenings and deaths, many recorded at Lion Walk Church, we find that Edward was commuting between London, Colchester and Newcastle during these years. Edward sounds like some sort of wholesale draper. He also inherited money, land and property from the death of his wealthy sister-in-law, who had no heirs. He was now seriously well off. Only one of his children survived, also named Edward.

Edward senior died in 1827 at his house in Priory Street, when his son was only 12. At that point he would inherit the bun, which was now 20-years-old. But why had it been kept? Bearing the mark of Christ’s cross, baked on Good Friday, such buns were superstitiously believed to have healing power. Households often kept a bun all year in their kitchen if a child was born, in case it got sick – and four out of five Holdich children died young. Was Edward was superstitious?

When Edward junior was 22 his mother re-married. Edward moved to London, possibly into the circle of his wealthy Holdich relatives.

HISTORY. Good Friday hot cross buns on sale in Regency England by the artist Thomas Rowlandson

At the 1841 Census he was living in Kennington, London, and was of independent means meaning he had so much money he didn’t have to work. And he didn’t work much the rest of life. Only at the census in 1851 did he have a job – that of chemist. He practised in Lavenham where he married Sophia Baker, daughter of a farmer. There were no children.

By 1861 he was retired and owned a large house, three servants, several horses, and a very old, crossed bun.

By 1881 his wife was dead, and he was living in Hackney with his wife’s nephew, George Baker, a commercial traveller, and his wife and baby son, George.

In 1887 Edward Holdich died in Suffolk, where he may have owned several houses. His executors were his nephew, George Baker and Harry Baker.

In the long task of going through Edward’s considerable belongings, which one saw the bun in the bag and said, “I’ll have that” ?

The answer is Harry Baker, draper of Sudbury. He lived until 1943 when his executor was his son-in-law, Norman Baker, a chartered accountant.

Only one question remains: where is Andrew Munson now? I hope he is still around. Is anyone in Wormingford reading this?

We need to tell the Munsons that their bun is genuine. And is it the oldest known? In 2011 the BBC and British Museum did a series called A History of the World in 100 objects.

It included a hot cross bun baked in 1869, now part of the museum’s collection and a source of some reverence. 1869? Is that all?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel