YOU will have probably gathered from this column that I favour the more random, obscure chapters in our town’s long and chequered history.

One such off-the-wall anecdote can be found in, of all publications, An Essex Christmas, compiled by Humphrey Phelps (Sutton 1993).

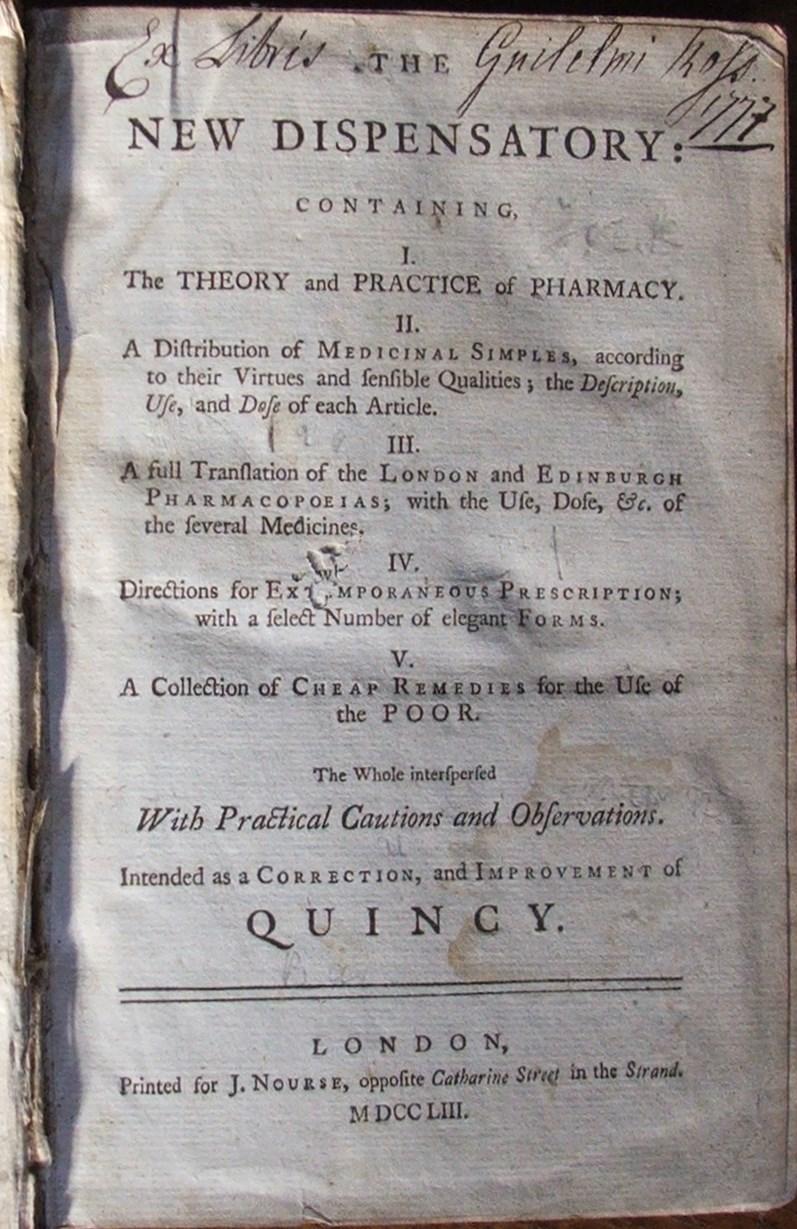

Although really nothing to do with the festive season, on page 17 there is a reproduction of a bizarre Georgian advertisement, placed in the Ipswich Journal by someone who styled themselves a ‘Doctor’.

Reading it made me think of those medicine men in Spaghetti Westerns. You know the sort, a dusty quack rides into a one-horse town and tries to hard sell his cure-alls before quickly moving on before he is discovered.

So picture the scene, not in the States, but here in Maldon.

It was November 1760 when the ‘Doctor’ with the unbelievably flamboyant name Mylock Pheyaro rode up Market Hill and into the High Street.

He was looking for somewhere to set up his temporary ‘surgery’ and it is clear from the previous places that he had been to that he favoured a pub.

He had been consulting and prescribing in a number of them in Suffolk (at Saxmundham, Woodbridge and Hadleigh) and north Essex (Manningtree and Wivenhoe) and had just finished his work at Colchester’s King’s Arms (aka the King’s Head and now the Hole in the Wall).

It would appear that in Maldon he chose the Crown.

We now know it as Wetherspoon’s Rose and Crown. It was formerly the Red Lion, but during the mid-18th Century changed to the Rose and Crown, and was often simply referred to as the Crown.

Ken Stubbings confirms that it was, indeed, the venue in his informative book Here’s Good Luck to the Pint Pot (Brown 1988), when he says “in 1760 a doctor ran surgeries there”.

So we are on the right trail, but what exactly was he up to?

We return to that advert, where he boasted at being able to cure a long list of many and varied illnesses.

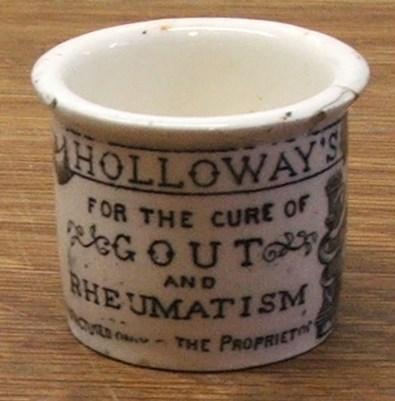

Some of them are still identifiable today, while others need further explanation. They included Cancerous Complaints (pretty broad and immediately suspicious), Fustulas (probably Fistula, now associated with bowel and intestinal complaints), King’s Evil (a skin disease often linked to TB – it was believed a royal touch could cure it), ulcers in legs and “other extremities”, Scurvy (from a lack of vitamin C), Pimples in the Face, St Anthony’s Fire (ergotism – muscle pain and much worse), Scald Heads (a disease of the scalp with hair loss), Itch, Gout and Rheumatism.

He then adds as a catch-all throwaway “and many other disorders too tedious to mention”.

What a clever physician he was – a super GP long before the days of the National Health Service.

But was it really all true? He claimed to have a good track record and said that “since June last” his success was “sufficient testimony of my ability and those who need my assistance may, with good effect, through the help of God, apply to their friend and humble servant”.

In fact there was even a patient who was prepared to go on record and put her name to his incredible medical skills.

Elizabeth Ford had had scurvy since her teens. None of the mainstream Maldon doctors had managed to help her, but Mylock Pheyaro had treated her and, hey presto, she was cured.

Odd – was she in his pay, did he really make a difference, was there some element of placebo effect involved?

The mind is a powerful thing, but there are some illnesses that need much more than that. As the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh has put it recently, “perhaps he had good communication skills, even if he had little in his saddlebag that could be offered as a cure, or lacked more solid evidence of the ‘truth’ about the effectiveness of his medicines and ministrations. One wonders what questions these patients must have asked of him, what information they brought to help support their treatment decisions and what degree of concordance they reached”.

Whatever the position, his advert has become an international medical curiosity and now even appears in Edzard Ernst’s Healing, Hype or Harm, a scientific investigation of complimentary or alternative medicine’ (Societas 2008).

Doctor Pheyaro was still in Maldon in September 1761, but then disappears from the record.

Perhaps things were getting a bit too hot for him here.

Visiting the Rose and Crown today, one wonders where the landlord, Thomas Brand, allowed him to put up shop.

Where did he meet his would be patients and where did they undress to show him their conditions?

Next time you pop in there for a pint or something to eat, if you think you can see a shadowy character in a dark recess wearing a tri-corn hat, whatever you do, don’t tell him how you are feeling.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here